Mexican independence from Spain brought change to trans Nueces

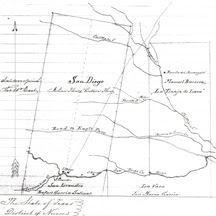

In 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain and ramifications of that historic change was felt in the trans Nueces region, including what would become Duval County. The Spanish state of Nuevo Santander seized to exist and the area between the Rio Grande and Nueces Rivers was now part of the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. On December 15, 1826 Mexico adopted Decree #42 that laid out new colonization laws. The laws allowed foreigners to colonize vacant lands in the state, provided they submitted to the decrees of the Republic and those of the state. No foreigners took up the Mexican government in the area around Duval County. The nearest such settlement was the McMullen and McGloin grant granted to the Irish in nearby San Patricio. The decree defined a sitio as a square league or 25 million square varas , a vara being three geometrical feet or about 32 inches. A labor was designated as one million square varas or 1,000 varas on each side of a square. The congress of Tamaulipas